Hopefully you have already looks at some of the "beginner" level Processing tutorials, such as:

- Hello Processing

- Getting Started

- Processing Overview

- Coordinate Systems and Shapes

- Color

- Trig Primer or this site's Sines, Cosines and All That.

You need to have worked through at least these tutorials to understand what follows, because I will be using techniques from each of them.

The first step in writing any program is to have a clear idea of what you want to achieve. If you do not have any idea of where you want to end up, you are very unlikely to get there. (OK! So journeys in art are often as much about exploration as following a well-defined route from A to B. The point is still valid: you need some initial ideas about where you might find interesting landscapes.)

This project is inspired by memories of a childhood toy - the "Spirograph" (see the Wikipedia entry) which produced designs such as these:

Spirograph was made with plastic gear wheels. By choosing various gear ratios and pen colours one could make a wide variety of figures featuring harmonic motions. (The figure on the right was copied from the Wikipedia page.) Interestingly, Spirograph is still available on the market today, so it still generates visual interest with young people.

Can we reproduce the figures generated by Spirograph using a computer program? (Obviously we can, but how?) This will provide us with a first project to explore how Processing can be used to work our way towards a definite visual goal.

In fact, it will soon become obvious that Processing allows us to go way beyond what was possible with Spirograph. We can, for example, make changing the gear ratios interactive, so we see immediately the effect of different choices. If we wish, we can also make some of the basic parameters vary with time. For example, we can gradually reduce the size of the gears, or we can blend colours rather than switching pens, or we can use nibs with more interesting shapes than a simple point.

Where do we start? We will certainly need to know how to draw a circle. If you have followed the Processing basic level tutorials, you will now know that you can draw a circle using the command such as ellipse(200,200,100,100);. (Reminder: this command says make the (x,y) position (200,200) the center of the figure and make the width and height (200,200), so this produces a circle of radius 100 pixels centred on a point 200 pixels from the left of the window and 200 pixels from the top.)

However, this will not do the trick for us. We need to make small circles run round the inside of big circles, so we are going to need to make them a step at a time as we rotate round the diagram. So, the first thing we need to do is learn how to draw a regular polygon, with a specified number of sides, and we will eventually make the number of side so big that we can no longer see the difference from a proper circle.

float r0 = 150.0; // The radius of our circle in pixels.

int nsides = 12; // The number of side in our regular polygon.

float ith = TWO_PI/nsides; // Increment in angle for each side of the figure.

int x0 = 200; // The centre of the polygon - x coordinate.

int y0 = 200; // The centre of the polygon - y coordinate.

void setup() // Executed once when Processing starts-up.

{

size(400,400); // Size of our canvas.

background(100); // Make the background colour grey.

stroke(255,255,255); // Draw the outline in white.

}

void draw()

{

for(int i=0;i<nsides;i++) // Draw a line for each side

{

float theta = i*ith; // Increment the angle each time round the loop.

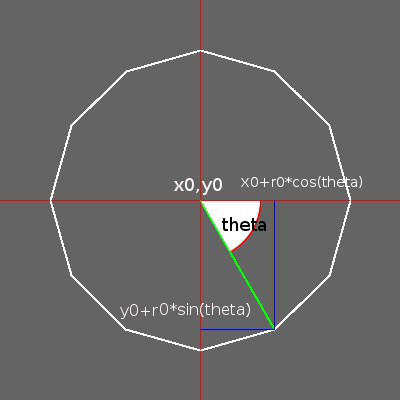

int x1 = x0 + int(r0*cos(theta)); // x position of start of each line.

int y1 = x0 + int(r0*sin(theta)); // y position of start of each line.

int x2 = x0 + int(r0*cos(theta+ith)); // x position of end of each line.

int y2 = x0 + int(r0*sin(theta+ith)); // y position of end of each line.

line( x1,y1, x2,y2); // draw the line.

}

}

|

This is the figure (in white) produced by the above program. (The coloured lines and annotations are a later addition, to aid explanation.) Already this simple program introduces a number of important points that need further comment.

|

|

So, we now have a method of drawing a polygon that can look as close as we like to a circle. We draw it by allowing the value of theta to go from 0 to 2*π radians. We are going to call this our first harmonic, for reasons that will become clear later.

Things only really start to get interesting when we introduce epicycles that correspond to the smaller gears in Spirograph. We could arrange for another circle to effectively roll around the inside of our first harmonic circle, but this introduces a bit of programming clutter that we do not really need. We can get exactly the same visual effects letting its center move along the circumference of our first-harmonic circle, but rotating from 0 to 2*π twice while we go round the first harmonic once. This is our second harmonic, and we will want to choose its radius to be anything we like. We carry on doing the same thing for third, forth, fifth harmonics and so on, each rotation going 3, 4 or 5 times as fast respectively. We will stop at the ninth for the time being - that is sufficiently complicated already. The program and some of the results are shown in the next page.

The following figure shows how epicycles work.

Instead of using just one sine and cosine to calculate a position on the locus of the epicyclic curve (and getting an approximation to a circle, we add a series of sines and cosines. Each additional term in the sum multiplies our basic iteration angle and the we assign a different radius (a "harmonic amplitude") to each term, getting two summed series which are used to calculate the next X and Y coordinates of the curve:

X = ∑ Rn cos(2π nθ)

Y = ∑ Rn sin(2π nθ)

Now start up Processing and cut and paste the following program into the edit window, and run it to see an animation. (Or else download the complete program here.)

// Variables defined here are "Global" that is, accessible to every sub-program for reading and writing.

// We need to declare here some of the variable whose values will be defined in the setup() routine

// and later used in the draw() routine and its sub-programs.

int xmax; // xmax and ymax will hold the x and y extent of the canvas,

int ymax; // which it is useful to hold in variables so we can refer to them by names.

int xc; // x0 and y0 will define the centre of the canvas

int yc; // which is often useful to refer to by name.

int hmax = 10; // Number of harmonics allows (including zeroth).

float[] r; // The radius of our epicycle harmonics in pixels.

float[] p; // Phases of each harmonic - these will be initialised in setup();

float[] f; // The relative frequency of each epicycle;

int nsides = 500; // The number of side in our regular polygon approximating the circle.

float ith = TWO_PI/nsides; // Increment in angle for each side of the figure.

// Note the use of radians (TWO_PI) for the total angle around a circle.

float tdeg = 180.0/PI; // Conversion factor from radians to degrees.

int count = -1; // For counting the number of times draw() has been called.

float x[];

float y[];

float x1[];

float y1[];

int cr[];

int cb[];

int cg[];

void setup() // Executed once when Processing starts-up.

{

size(1000,1000); // Size of our canvas - has to be explicit integers by Processing rules.

xmax = width; // It is useful to refer to the canvas size symbolically

ymax = height; // so we can remember what we mean when using "400" etc..

xc = xmax/2; // We can now work out the coordinates of the canvas centre.

yc = ymax/2; //

r = new float[hmax]; // Array of harmonic amplitudes

p = new float[hmax]; // Array of harmonic phases

f = new float[hmax]; // The harmonic frequencies.

x = new float[hmax]; // Used to draw the circle radii - x[i] coordinate of current circumference point on i'th circle

y = new float[hmax]; // Used to draw the circle radii - y[i] coordinate of current circumference point on i'th circle

x1 = new float[nsides+1]; // This remembers the x-coordinates of the points used to define the final figure.

y1 = new float[nsides+1]; // This remembers the y-coordinates of the points used to define the final figure.

cr = new int[hmax]; // Array to be used for Red colour component for each harmonic figure.

cg = new int[hmax]; // Array to be used for Green colour component for each harmonic figure.

cb = new int[hmax]; // Array to be used for Blue colour component for each harmonic figure.

for(int h=0;h<hmax;h++)

{

r[h] = 0.0; // Need to ensure that all circle radii are initialised - set all to zero to start with.

p[h] = 0.0; // Phases not used.

f[h] = 1.0+(h-1)*1; // Set frequencies to be n=k*mod(m) to give (m-1)-fold figure symmetry.

cr[h] = 200; //

cg[h] = 200;

cb[h] = 200;

}

r[0] = width/5; // The fundamental size scale;

r[1] = 1.0; // The first harmonic amplitude. (I.e radius of first circle.)

r[2] = 0.8; // The second harmonic amplitude. (I.e. radius of second circle.)

r[3] = 0.4; // The third harmonic amplitude. (I.e. radius of third circle.)

r[4] = 0.2; // The fourth harmonic amplitude. (I.e. radius of fourth circle.)

cr[1] = 0; cg[1] = 0; cb[1] = 200; // Define colour to use for first harmonic circle

cr[2] = 200; cg[2] = 0; cb[2] = 0; // Define colour to use for second harmonic circle

cr[3] = 0; cg[3] = 200; cb[3] = 0; // Define colour to use for third harmonic circle

cr[4] = 0; cg[4] = 200; cb[4] = 200; // Define colour to use for fourth harmonic circle

background(100,100,100);

frameRate(50); // Make this smaller if you want more time to see what is happening.

}

void draw()

{

count++;

translate(xc,yc); // Make origin of coordinate system the centre of the drawing area.

float theta = count*ith; // The angle made from the horizontal by the line

// from the polygon centre to the current vertex.

if(count <= nsides)

{

background(200); // Make the background colour grey - erasing everything

// from the last time draw() was executed.

x1[count] = 0.0;

y1[count] = 0.0;

x[0] = 0.0;

y[0] = 0.0;

for(int h=1;h<hmax-1;h++) // Leave f[9] for perp line

{

stroke(255,255,255,30); // Draw the outline in white.

fill(cr[h],cg[h],cb[h],30); // Fill with a harmonic specific colour specified in setup()

ellipse(x1[count],y1[count],2*r[0]*r[h],2*r[0]*r[h]); // Draw a circle centred at the position specified by the sum of previous harmonics.

x1[count] = x1[count] + r[0]*r[h]*cos(f[h]*(theta+p[h])); // Accumulate the sum of x components of each circle's radius

y1[count] = y1[count] + r[0]*r[h]*sin(f[h]*(theta+p[h])); // Accumulate the sum of y components of each circle's radius

x[h] = x1[count]; // Remember the partial sum so we can draw each circle radius.

y[h] = y1[count];

strokeWeight(3);

stroke(cr[h],cg[h],cb[h],100);

line(x[h-1],y[h-1],x[h],y[h]); // Line from the centre of the current circle to its current circumference point.

}

}

strokeWeight(2);

stroke(255,255,255,100);

for(int i=1;i<=nsides;i++) // Draw (or redraw) all parts of the polygon calculated so far.

{

line( x1[i-1],y1[i-1], x1[i],y1[i]); // draw the line giving one segment of the polygon.

}

}

It becomes a bit tedious to experiment with different figures by varying the amplitude and phase of the harmonics by each time stopping the program, modifying the values defined in setup() and restarting. We can interactively modify amplitudes by adding the following sub-programs. These respond to mouse movement and key-presses and interactively modify amplitudes and phases.

void keyPressed()

{

if(key == '0' ) { r[0] = float(mouseX)/2.0;}

if(key == '1' ) { r[1] = float(mouseX)/float(xmax); p[1] = TWO_PI*float(mouseY)/float(ymax);}

if(key == '2' ) { r[2] = float(mouseX)/float(xmax); p[2] = TWO_PI*float(mouseY)/float(ymax);}

if(key == '3' ) { r[3] = float(mouseX)/float(xmax); p[3] = TWO_PI*float(mouseY)/float(ymax);}

if(key == '4' ) { r[4] = float(mouseX)/float(xmax); p[4] = TWO_PI*float(mouseY)/float(ymax);}

if(key == '5' ) { r[5] = float(mouseX)/float(xmax); p[5] = TWO_PI*float(mouseY)/float(ymax);}

if(key == '6' ) { r[6] = float(mouseX)/float(xmax); p[6] = TWO_PI*float(mouseY)/float(ymax);}

if(key == '7' ) { r[7] = float(mouseX)/float(xmax); p[7] = TWO_PI*float(mouseY)/float(ymax);}

if(key == '8' ) { r[8] = float(mouseX)/float(xmax); p[8] = TWO_PI*float(mouseY)/float(ymax);}

if(key == '9' ) { r[9] = float(mouseX)/float(xmax); p[9] = TWO_PI*float(mouseY)/float(ymax);}

}

The subroutine responds to a key-press, and reads the current position of the mouse. For example, if key "2" is pressed, then the horizontal position of the mouse in the canvas is used to determine a new amplitude of the 2nd harmonic and the vertical position the phase offset. When the "0" key is pressed the horizontal position is used to determine the overall scale of the figure.

We will also find that we want to save images from our programs. In particular, we may want to save an image while a figure is building up over time. To do this we can include the following subroutine.

void keyReleased()

{

// This is called by the Processing system once whenever a key is released.

// The value of the key is stored in the "key" global variable.

// We use the "released" event as a user signal for certain actions

// because we can guarantee that it is a discrete event.

// (In contrast the keyPressed() routine is called multiple times while a key is held down.)

if(key == 's') { saveFrame("Output-####.jpg");} // Save a copy of the current image as a JPEG file.

// The name of the time is constructed according to

// the exact time the event was actioned so multiple

// requests always generate new files.

if(key == 'e') { background(200,200,200);} // Erase the previous figure and create a new background.

}

Pressing the "s" key saves a JPEG image. It will have a name of the form "Output-####jpg" where #### is replaced by a unique integer so we can save multiple images from our program run. The above program also include an erase operation that occurs when the "e" key is presssed.

The following figures show two versions of epicycle generation with interactive control.

| In this sketch, after the curve has finished drawing, you can put the mouse inside the figure click it and then press one of the numerical keys. It will redraw the figure with the amplitude and phase of the harmonic component corresponding the number of the key modified. Moving the mouse left to right changes the amplitude of the harmonic, moving it up and down changes the relative phase. | |

| This figure also draws epicycles, but modifies the complete curve interactively. Again, click with the mouse on the figure, then depress one of the numerical keys and keep it depressed while you move the mouse. It will redraw the figure with the amplitude and phase of the harmonic component corresponding the number of the key modified. Moving the mouse left to right changes the amplitude of the harmonic, moving it up and down changes the relative phase. |

See my Harmonics page for a more in depth discussion of Fourier Series and an further example of using epicycles to produce a square!

Now let us see how we can use this to produce some more interesting images, using a slightly more elaborate program described on the next part.

We now have all the parts in hand. The program below has been used to generate most of the figures in the "Epicycles" Gallery. However, just pressing the "Run" button produces a rather boring image - a fuzzy circle. All we are seeing here is the first harmonic - a circle, where the points that are iterated over on the curve are each given an additional small motif - a short line perpendicular to the curve and one at a tangent to the curve.

Things only become interesting when we start to use the interactive features. That is where you start to add value to the generated image. Outputs from the example program (above) illustrates what is possible. The example program below show how epicycle curves are constructed - this just shows the setup() and draw() parts of the program. (The full program including additional subroutines, keypressed() and keyReleased(), for interactivity and saving images can also be downloaded here.) Just paste it into the Processing code window and run.

// Variables defined here are "Global" that is, accessible to every sub-program for reading and writing.

// We need to declare here some of the variable whose values will be defined in the setup() routine

// and later used in the draw() routine and its sub-programs.

float ampr=50; // Amplitude of variation of RED component of colour.

float ampg=200; // Amplitude of variation of GREEN component of colour.

float ampb=55; // Amplitude of variation of BLUE component of colour.

int r_zero = 10; // Level around which R component varies with amplituded ampr;

int g_zero = 100; // Level around which G component varies with amplituded ampg;

int b_zero = 200; // Level around which B component varies with amplituded ampb;

float p_red = 0.7; // Number of radians that takes R component through its full range of variation.

float p_green = 0.8; // Number of radians that takes G component through its full range of variation.

float p_blue = 0.9; // Number of radians that takes B component through its full range of variation.

float dpr;

float dpg;

float dpb;

int xmax; // xmax and ymax will hold the x and y extent of the canvas,

int ymax; // which it is useful to hold in variables so we can refer to them by names.

int xc; // x0 and y0 will define the centre of the canvas

int yc; // which is often useful to refer to by name.

int hmax = 10; // Number of harmonics allows (including zeroth).

int hmode = 0;

float[] r; // The radius of our epicycle harmonics5 in pixels.

float[] p; // Phases of each harmonic - these will be initialised in setup();

float[] f; // The relative frequency of each epicycle;

int nsides = 10000; // The number of side in our regular polygon approximating the circle.

float ith = TWO_PI/nsides; // Increment in angle for each side of the figure.

// Note the use of radians (TWO_PI) for the total angle around a circle.

float tdeg = 180.0/PI; // Conversion factor from radians to degrees.

int count = 0; // For counting the number of times draw() has been called.

void setup() // Executed once when Processing starts-up.

{

size(1200,1200); // Size of our canvas - has to be explicit integers by Processing rules.

xmax = width; // It is useful to refer to the canvas size symbolically

ymax = height; // so we can remember what we mean when using "400" etc..

xc = xmax/2; // We can now work out the coordinates of the canvas centre.

yc = ymax/2; //

r = new float[hmax]; // Array of harmonic amplitudes

p = new float[hmax]; // Array of harmonic phases

f = new float[hmax]; // The harmonic frequencies.

dpr = TWO_PI/p_red; // Increment of RED phase

dpb = TWO_PI/p_blue; // Increment in BLUE phase

dpg = TWO_PI/p_green; // Increment in GREEN phase

for(int h=0;h<hmax;h++)

{

r[h] = 0.0;

p[h] = 0.0;

f[h] = 1.0+(h-1)*5; // Set frequencies to be n=k*mod(m) to give (m-1)-fold figure symmetry.

}

r[0] = width/5; // The fundamental size scale;

r[1] = 1.0; // The first harmonic amplitude. The rest initialised to zero in setup();

r[9] = 0.1;

background(200,220,220);

stroke(255,255,255,50); // Draw the outline in white.

}

void draw()

{

count++;

translate(xc,yc); // Make origin of coordiante system the centre of the drawing area.

//background(100); // Make the background colour grey - erasing everything

// from the last time draw() was executed.

//r[0] = r[0]*0.995;

for(int i=0;i<nsides;i++) // Iterate round the vertices of the polygon approximating a circle

{

float theta = i*ith; // The angle made from the horizontal by the line

// from the polygon centre to the current vertex.

// Define current rgb colour

int red = r_zero +int( ampr*sin( dpr*theta ) );

int blue = b_zero +int( ampb*cos( dpb*theta ) );

int green = g_zero +int( ampg*sin( dpg*theta ) );

float x1 = 0.0; //

float y1 = 0.0;

float x2 = 0.0;

float y2 = 0.0;

float x3 = 0.0;

float y3 = 0.0;

//if(pflag == -1 && i == 0) {pflag = 1;}

for(int h=1;h<hmax-1;h++) // Leave f[9] for perp line

{

x1 = x1 + r[h]*cos(f[h]*(theta+p[h]));

y1 = y1 + r[h]*sin(f[h]*(theta+p[h]));

x2 = x2 + r[h]*cos(f[h]*(theta+p[h]+ith));

y2 = y2 + r[h]*sin(f[h]*(theta+p[h]+ith));

x3 = x3 + r[h]*cos(f[h]*(theta+p[h]+ith*2));

y3 = y3 + r[h]*sin(f[h]*(theta+p[h]+ith*2));

}

x1 = x1*r[0]; y1 = y1*r[0];

x2 = x2*r[0]; y2 = y2*r[0];

x3 = x3*r[0]; y3 = y3*r[0];

stroke(255,255,255,5);

line( x1,y1, x2,y2); // draw the line giving one segement of the polygon.

// The geometry here is not trivial, it is about finding the angle of bend

// at each vertex of the polygon and then bisecting it to draw a line perpendicular to the curve,

// and also establish tangent lines at right angles to the perpendicular.

// Expect to have use your large-size thinking cap if you want to work out what is going on here.

float theta1 = atan2((y2-y1),(x2-x1)); if(theta1 < 0.0) { theta1 = TWO_PI+theta1;};

float theta2 = atan2((y3-y2),(x3-x2)); if(theta2 < 0.0) { theta2 = TWO_PI+theta2;};

float dtheta=theta2-theta1;

if(theta2 > theta1)

{

dtheta = PI+theta2-theta1;

}

else

{

dtheta = TWO_PI+PI + theta2-theta1;

}

if(dtheta < 0.0) {dtheta = TWO_PI - dtheta;}

float alpha = PI-dtheta/2.0;

float x4 = x2 + r[0]*r[9]*cos( theta1 -alpha ) ;

float y4 = y2 + r[0]*r[9]*sin( theta1 -alpha ) ;

float x5 = x2 + r[0]*r[9]*cos( theta1 -alpha - HALF_PI) ;

float y5 = y2 + r[0]*r[9]*sin( theta1 -alpha - HALF_PI ) ;

float x6 = x2 + r[0]*r[9]*cos( theta1 -alpha + HALF_PI ) ;

float y6 = y2 + r[0]*r[9]*sin( theta1 -alpha + HALF_PI ) ;

stroke(red,green,blue,5);

line( x2,y2, x4,y4); // Make a line perpendicular to the curve.

line( x2,y2, x5,y5); // Make for rearward moving tangent line.

line( x2,y2, x6,y6); // Make a forward moving tangent line.

}

}

The first thing we may wish to do is adjust the amplitudes of the higher harmonics, by pressing the numerical keys and moving the mouse. Note that the images overlap while we are doing this. (We can erase and start again by pressing the "e" key.) The "0" key changes to overall scale of the figure and in this implementation the "9" key changes the size of the motif drawn at each point on the curve.

You can alter the length of a perpendicular line drawn at each point on the curve by holding down the "p" key and moving the mouse, and a tangent line to the curve with the "t" key and mouse. Note that the lines are drawn with a low opacity so the figure takes time to build up.

All the figures in the gallery are produce by interactive manipulations of these keys, and saved by pressing the "s" key. None of the figures are easily reproducible in that one would need to follow the same set of interactive operations exactly. You must experiment to see what can be achieved (and it is a surprising variety of forms).

You might like to play around with the line in setup() that says "f[h] = 1.0+(h-1)*5;". This expression has the effect that when we press the "3" key we are not getting the third harmonic, but one with frequency multiple defined by "1+ (3-1)*5", that is, 11. If we press the "4" key we get a frequency multiple "1+(4-1)*5", or 16. The "5" in this expression guarantees a five-fold symmetry in the final figure. Changing it to 3 or 4 or 6 or 11 would give higher rotational symmetries.

You might also like to play with the configuration parameters that affect the cycling of the colours.

Experiment!

What you need to do now is understand each line of the example above, and then try making some changes to achieve different effects.

The major characteristic of these epicyclic curves is that for each frequency component with have a cosine function controlling motion in the x direction and a corresponding sine function (that is, a cosine with a 90o phase shift) of the same frequency and amplitude controlling motion in the y direction. Things can get interesting if the allow the amplitudes and the phases to be different. We get Lissajous Curves. This is the subject of my next investigation - this time inspired by memories of playing with oscilloscopes and signal generators during lab work.